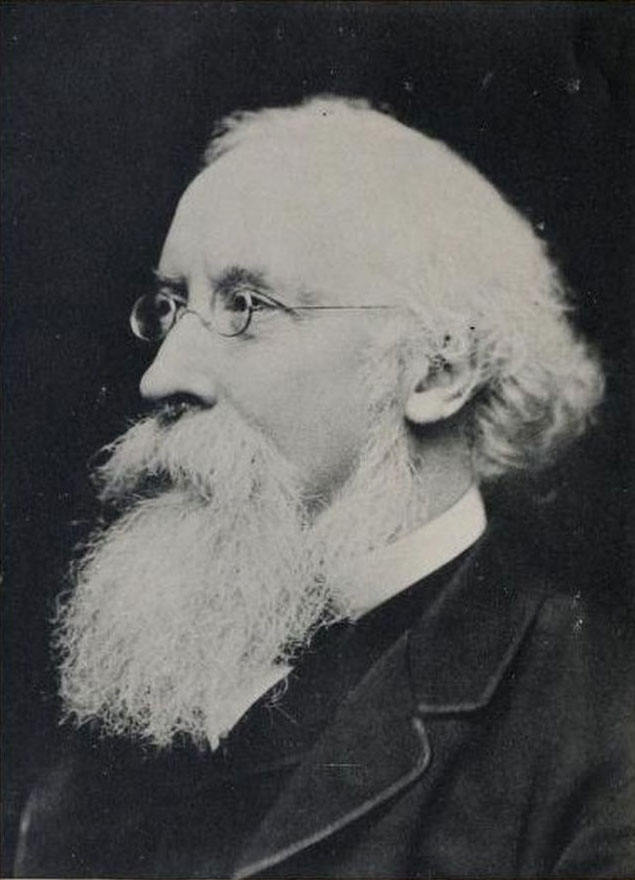

Whitley Stokes

Whitley Stokes was born in Dublin, into one of Ireland’s most prominent academic families. His father and grandfather were both professors of medicine at Trinity College Dublin. Throughout his life, Stokes’s social circle included many leading intellectuals, historians, artists, and writers: from his earliest childhood years, these included his father’s friends, the Irish antiquarians and scholars Samuel Ferguson, Eugene O’Curry, George Petrie and William Wilde (father of Oscar); later, Stokes became friends with the poet William Allingham and with the philologist Rudolf Siegfried. He was educated first at home and then briefly at St Columba’s College before he entered Trinity College Dublin. In 1851 Stokes went to London to study law and he was called to the Bar in 1855. During his ten years in London he befriended a variety of poets, artists, academics and other intellectuals who were at the heart of a vibrant literary and cultural scene. The best known of these are the Rossettis – Dante Gabriel, Christina and William Michael – and A. C. Swinburne. He left London in 1862 for India, where he worked for the legislative council; in 1879 he became president of the India Law Commission. After twenty years in India, Stokes returned to London in 1882, where he lived, at Grenville Place, Kensington, until his death in 1909. He is buried at Paddington Old Cemetery in Kilburn.

From the 1850s onwards, Stokes published prolifically on many topics, such as Serbian, Danish and Sanskrit poetry, but his most important contributions were to two fields: Anglo-Indian law and medieval Celtic philology and literature. The bibliography of his published works includes some thirty monographs and more than three hundred scholarly articles. In the field of law, his major works included Hindu Law Books (1865) and The Anglo-Indian Codes (1887-8). His seminal publications in the field of Celtic Studies are too numerous to mention; he edited and translated many of the most significant works of medieval Irish narrative literature, and it remains the case that many of these texts are only available in print today in Stokes’s editions and translations. In addition, he published many important philological studies on Old Irish glosses, as well as on Breton, Cornish, Welsh, and the gradually emerging remains of the Continental Celtic languages. Although he never held an academic post, he was an internationally renowned scholar, a founding Fellow of the British Academy, establishing and maintaining intellectual links, particularly with Germany, France and his home country, Ireland.

Stokes was a complex, contradictory and contrarian individual. Renowned for his acerbic, even aggressive, criticism of his contemporaries in print, Stokes’s private correspondence reveals him to be witty, warm and romantic. He suffered from strong feelings of depression and insecurity, which he described with surprising frankness in letters to his sister, the art historian Margaret Stokes (1832-1900). But the achievements of his life chart the expansion and consolidation of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, and raise questions about the experience of the Irish within that imperial context; and equally they chart the expansion and consolidation of historical and cultural knowledge within the nascent disciplines of philology and literary studies.